This post contains information some people may find distressing.

Having had a radical hysterectomy, including removal of my appendix and omentum, in what they call debulking surgery, three weeks earlier, I was now due to see the surgeon for my post-surgery follow up appointment and to get the results from the histology. They had sent the ovarian cyst, biopsies and washings from inside my pelvic cavity for testing at a laboratory to see if I had cancer. Essentially this was judgement day.

From the moment I had seen blood in my underwear I had been certain this was cancer. It appeared the ultrasonographer and doctors at the hospital, when I went to accident & emergency with a rapidly growing pelvic swelling less than a week later agreed with me. Nevertheless my CA-125 blood test for cancer markers had me firmly in the normal range, so there was still hope for a different outcome. The surgeon wouldn’t be drawn on whether it was cancer when she came to see me after my operation, so it had been a waiting game. I’d spent three weeks maintaining that it was most likely cancer and anything else would be a joyous surprise.

This appointment was my first outing since the surgery and involved another uncomfortable car ride. However, I was in much better shape than when I had been discharged from the hospital after surgery. My recovery had gone pretty well overall. My external scar was healing nicely and I was finding it easier to move around. Getting out of bed didn’t involve the struggle it had when I first came home. I still followed the recommended procedure of rolling onto my side and using my arm to pull me up and out of the bed, without using any damaged abdominal muscles. Now, however, I could be up in less than a minute whereas it had taken much longer and a lot of pain when I first got home. My bowels and bladder were working normally and I could even twist around to wipe myself now. My pain was much reduced and I was simply taking occasional painkillers not a regular regime of maximum dose daily.

I was very relieved that many of the post operative side effects had not come to pass. I had been particularly freaked by vaginal cuff dehiscence. This is a rare but very serious side effect of a radical hysterectomy. It is where the internal scar where the cervix was removed ruptures or separates. In the worst case scenario the bowels then push through the torn vaginal cuff. The thought of this had kept me following the bed rest and no lifting heaving objects assiduously. The advice to follow abstinence from sexual activity was unnecessary. I’d love to know who wants to participate in penetrative sex immediately after a hysterectomy!

I had had some post operative bleeding but nothing untoward and totally in line with what I should have done. I’d been following the diet to avoid a blocked bowel and staying well hydrated. I’d followed the instructions on how to empty my bowel well and safely and become good friends with my potty squatter (a small stool that goes in front of the toilet so you can put your feet on it when you go to the toilet, raising your knees above your hips and helping your bowels work more easily). I was using laxatives as prescribed and monitoring when I sent and whether what I produced was nicely in the middle of the “stool scale”. I continued to have many more conversations about my bowel habits than I had had in the entirety of the last decade! I had been doing my pelvic floor exercises from the day I returned home and was not finding any issues with urinary incontinence. With so many risks and things that could potentially have gone wrong I was feeling very blessed to have a good recovery. When my appointment came around my surgeon was also pleased with my recovery and felt I was progressing better than she expected at this point.

We quickly got to reviewing the laboratory results. The histology showed that my cyst had been malignant. It was cancer. Even though I had firmly believed from day one that it was cancer, it is still a shock. Hope is the last to die. I had continued to hold a secret hope that the ultrasound and CT scan findings were wrong and the CA-125 cancer marker blood test was right. I know my husband had been clinging much more firmly to the negative cancer marker blood test than me. Nevertheless I had continued to hope for good news. It was not to be.

The good news was that there was no evidence of cancer anywhere else. The biopsies and flushing had come back negative. The cancer was confined to the ovarian cyst, which had been removed in full. On this basis it would have been staged as Stage 1. Or Stage 1C2 to be specific. This is where cancer cells are found in one or both ovaries (or fallopian tubes). The ovary tissue (the capsule) burst before surgery or there’s evidence of cancer on the surface of at least one of the ovaries or fallopian tubes. However, the cyst had also stuck to my bowel and had to be detached during my surgery. On this basis my surgeon was classing my cancer as Stage 2. In Stage 2A Cancer cells have spread onto the womb and/or fallopian tubes. In Stage 2B Cancer cells have spread to other organs in the pelvis, for example the bladder or rectum (the last part of the large bowel before the anus, where waste leaves the body).

As well as being staged for spread (which most people are familiar with), cancers are also graded for how abnormal the cells are compared to healthy cells (which many people are less familiar with). Grade 1 are well differentiated cancers, with cells that closely look like normal cells and are less likely to spread or recur (come back). Grade 2 are moderately differentiated cancers. Grade 3 are poorly differentiated cancers, that show increasing difference of appearance compared to normal cells. They are also more likely to spread and come back. Mine was Grade 3. The one time you don’t want the top score.

Naturally, I had been checking ovarian cancer survival rates in preparation for this appointment. At Stage 1 almost 95% of women will survive their cancer for five or more years after their diagnosis. At Stage 2 almost 70% of women will survive their cancer for 5 or more years after their diagnosis. At Stage 3 almost 25% of women will survive their cancer for 5 or more years after their diagnosis. At Stage 4 almost 15% of women will survive their cancer for 5 or more years after their diagnosis. For women with ovarian cancer in England more than 70% will survive more than one year after they are diagnosed. Almost 45% will survive five or more years after diagnosis. Almost 35% will survive ten years or more.

Your outcome depends on the stage of the cancer when it was diagnosed. The type and grade of ovarian cancer affects your likely survival. Your grading also has an impact. Your likely survival is also affected by whether the surgeon can remove all the tumour during initial surgery. Your general health and fitness may also affect survival. Lower graded cancers have a better outlook. Age also affects outcome and survival is better for younger women.

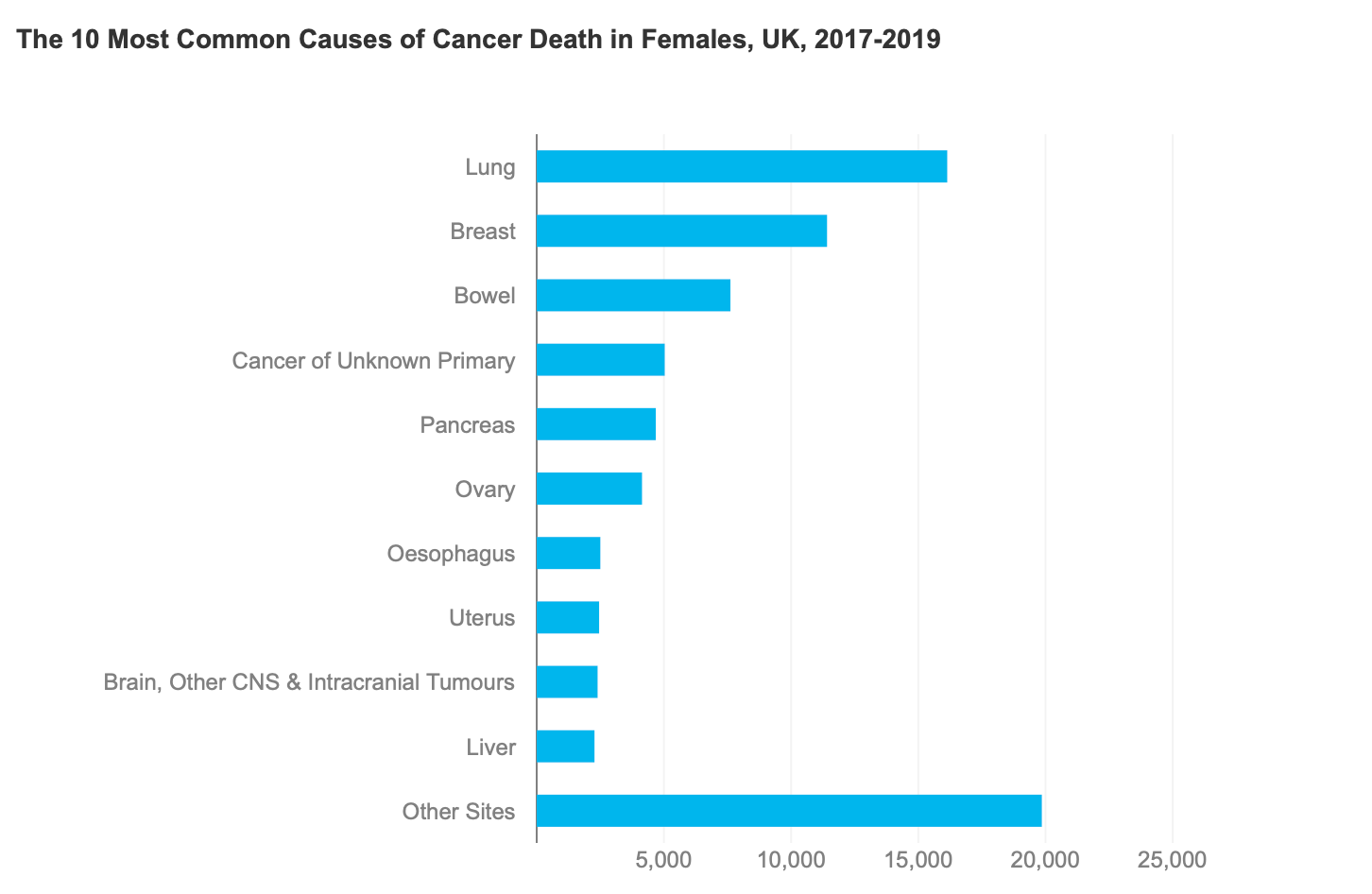

Cancer kills one in four people annually. That is around 167,000 deaths annually. About 47% of which are women. Almost half of these cancer deaths are lung, bowel, breast or prostate cancer. Since the 1970s mortality rates for all cancers combined have decreased by about a fifth. Rates in female cancers have decreased by about a seventh.

There are around 7,500 cases of ovarian cancer annually in the U.K. In females, ovarian cancer is the 6thmost common cancer. Since the early 1990s ovarian cancer rates have remained stable. There is no screening programme for ovarian cancer. The incidence of ovarian cancer is expected to rise 5% between 2023 and 2040.

A woman’s risk of developing ovarian cancer in her lifetime is 1 in 87. Her risk of dying from invasive ovarian cancer is 1 in 130. Ovarian cancer survival rates are much lower than other cancers which affect women. Incidence is higher in women aged 75 and over. Incidence is lower in women from black, Asian or mixed race.

Up to 20% of ovarian cancers are caused by a change to one or more genes known to increase the risk of ovarian cancer. This gene will have been passed down through families. Some types of ovarian cancer (e.g. high grade serous epithelial ovarian cancer) are more likely to be caused by this hereditary gene. Some hereditary ovarian cancers make you more prone to developing other cancers, such as breast cancer. Your consultant can arrange gene testing for you. With a strong family history of cancer, which included breast, suspected ovarian, pancreatic and prostate cancer (all of which can indicate the hereditary gene) I elected to have gene testing.

There are several different types of ovarian cancer. The type of cancer depends on the type of cell and tissue the cancer starts in. There are three types of ovarian cancer: epithelial, germ cell and sex-cord stromal. Each of these has several subtypes. Some types of ovarian cancer are more common than others and affect women at different ages.

Epithelial ovarian cancer is the most common type of ovarian cancer, accounting for around 90%. It starts in the cells that lines or cover the ovaries and fallopian tubes (the epithelium). Not all epithelial tumours will be cancerous (malignant), some will be non-cancerous (benign). There are several subtypes of epithelial ovarian cancer: High grade serous, low grade serous, endometroid, clear cell, mucinous, brenner, ovarian carcinosarcoma and finally unclassified / undifferentiated.

I had Endometroid Adenocarcinoma. Endometroid ovarian cancer accounts for around 20% of epithelial ovarian cancer cases, so is technically a rarer ovarian cancer. This type affects women of all ages, and it can be linked to endometriosis. It’s commonly treated with a combination of surgery and chemotherapy.

On the basis of a Stage 2 diagnosis and despite my surgeon having removed my tumour completely, the next step for me was chemotherapy. This is what is called adjuvant chemotherapy, or preventative as many people describe it. The goal is to lower the chance of cancer coming back. Because even if all visible cancer is removed during surgery, there still may be some remaining in the body that can't be seen. Even if something microscopic was left behind, it is very likely to lead to a recurrence of the cancer. I was fully on board with nuking any remaining cancer cells!

I would be referred to a clinical oncologist who specialises in using chemotherapy to treat cancer. The standard protocol for my type, stage and grade of ovarian cancer would be to have a course of six infusions of chemotherapy over 18 weeks. I would be treated every 3 weeks and receive two drugs, Paclitaxel and Carboplatin. I would have another CT scan at the end of the 6 cycles and if there was no evidence of disease then I would require no further treatment. My priority now was to get in to see the clinical oncologist and start treatment as soon as possible.

If you’ve experienced something similar or have any questions, please leave a comment below. I’d love to hear your thoughts and experiences.

For more updates and health tips, don’t forget to subscribe to our newsletter. Share this post with your friends and family to spread awareness about the importance of early detection in gynaecological health.

Stay healthy and take care!

Thanks for sharing so honestly Sarah. Rooting for you always :) Love Sarah & the DB team x

This is my journey exactly! Same type, treatment etc but mine was 1c - I am nearly 2 years down the road and back on track. Good luck with your journey and love reading them! Thank you